The position in which thought finds itself after 1945 forces Hannah Arendt to

leave the realm of philosophy and turn to literature. Only there does she encounter

the question preoccupying her. In her “Preface: The Gap Between Past and

Future,” which precedes the essays of her 1961 volume Between Past and Future,

the moment in which she moves into a reading of Kafka is rooted in an experience

that refers to the relation between thought and reality: “reality has become

opaque for the light of thought.”1 For Arendt, the present Now in which she writes

and thinks is marked by the fact that thinking and reality are no longer linked

with one another. Thought does not withstand the shock of reality. Therefore,

thinking - “no longer bound to incident as the circle remains bound to its focus” -

risks “either […] becom[ing] altogether meaningless” or relying on truths that

have been passed down, “old verities which have lost all concrete relevance.”2

Through the quote from René Char's Feuillets à Hypnos [Leaves of Hypnos] that

introduces her essay - “Notre héritage n'est précédé d'aucun testament - 'our

inheritance was left to us by no testament'”3 - Arendt's reflections on the divergence

of thinking and reality are temporally and logically connected back to the

time of the resistance and to the realization of the abyss into which the grounds

of reality, der Boden der Tatsachen, have changed, as she writes in an earlier text.

So it is the wish to describe this particular situation in exact terms that leads

Arendt to Kafka. She reads Kafka's text - an account from the series of the “He”

pieces from 19204 - as a “parable.” In this term, she follows the word's etymological

traces of meaning (para, next to, and ballein, to throw) and describes the

text as a kind of missile of rays, which sheds light on the hidden inner structure

of occurrences. It is precisely in this image that she sees the singularity of Kafka's

literature. These rays of light, “thrown alongside and around the incident […]

do not illuminate its outward appearance but possess the power of X rays to lay

bare its inner structure that, in our case, consists of the hidden processes of the

mind.”5

Kafka's text constructs a thought-image in which a man, “he,” is caught

between two antagonistic forces: “The scene is a battleground on which the

forces of the past and the future clash with each other; between them we find

the man whom Kafka calls 'he,'' who, if he wants to stand his ground at all, must

give battle to both forces.”6 Arendt emphasizes that the time currents of the past

and the future collide as antagonistic forces only because “he” is already there:

“the fact that there is a fight at all seems due to the presence of the man.”7 The

term “presence” here emerges in its spatial connotation. Arendt's commentary

moves back and forth between “the human being” and the “he,” the pronoun

that occurs in Kafka's text; this oscillation thereby signals how the contradiction

between the universal and the singular in her reading is at once opened up and

settled. “Seen from the viewpoint of man,” she notes, time is not a continuum;

rather, it is precisely “at the point where 'he' stands,”8 broken or cracked open. In

the course of Arendt's reading, her formulation of “the point where 'he' stands” -

in which the place available to “him” has shrunk to an extreme minimum, to a

point on a line - translates itself into the “standpoint,” addressing the capacity

of judgment: “'his' standpoint is not the present as we usually understand it but

rather a gap in time which 'his' constant fighting, 'his' making a stand against

past and future keeps in existence.”9 Thus, Arendt's interpretation introduces the

figure of speech of the “ground under one's feet” [Boden unter den Füßen] and

links it to a reflection on temporality by reading it as an “insertion in time”: “Only

because man is inserted into time and only to the extent that he stands his ground

does the flow of indifferent time break up into tenses.”10 For Arendt, it is precisely

this insertion, this point of rupture in the indifferent flow of time, that marks the

beginning of a beginning, as she writes with recourse to Augustinus.

Kafka's “he,” in its third-person singular form, appears as a pronoun that

designates a person who can jump out of the line of battle only in dreams. In this

sense, one can claim that the form of grammatical speech in Kafka's text enacts

the tension, or perhaps even the conflict, between the singular and the universal:

the “he” in Kafka at once opens and limits generalization; it does not mediate

between the singular and the universal. Arendt, however, wishes to develop a

generally valid metaphor for the activity of thinking via her insertion of and commentary

on Kafka's text. She searches for a metaphor that allows her to think the

activity of thinking in such a way that it is bound to and remains anchored in the

present - “rooted in the present.”11 Thus, she is concerned with a thinking that

remains embedded in “human time”12 and does not surrender to “the old dream

which Western metaphysics has dreamed from Parmenides to Hegel of a timeless,

spaceless, suprasensuous realm as the proper region of thought.”13 Arendt brings

the jump of which Kafka's “he” “at least” dreams, namely, that “some time in an

unguarded moment - and this would require a night darker than any night has

ever been yet - he will jump out of the fighting line,”14 into accord with the jump

that thought makes from human time into the timeless sphere of metaphysics, as

passed on in the Western history of philosophy.

For Arendt, Kafka's “he” has barely enough room to stand, because Kafka

clings to the traditional image that presents time as a straight line.15 She replaces

the figure of the line with a parallelogram. According to her argument, this form

comes into being due to the mere fact that the “he” is imprisoned in the flow of

time: “The insertion of man, as he breaks up the continuum, cannot but cause

the forces to deflect, however lightly, from their original direction.”16 This tiny

deflection of powers allows something spatial, an angle, to appear, and so the

geometric metaphor changes: the line becomes a plane. Or in Arendt's words: the

interval, the gap where “he” stands, becomes something like a parallelogram of

forces. Yet what is decisive for the genesis of this metaphor of the activity of thinking,

which Arendt gleans from her reading of Kafka, is that now the point where

the forces collide becomes the origin of a third figure: namely, a diagonal line.

Exactly inverting the two forces that meet in the point, this diagonal force would

be limited from its point of origin but infinite with regard to its end. The movement

of thinking expressed in this image would thus have a determined direction

through past and future, yet at the same time it would not be completable. Arendt

describes the figure constituted in this way as a “small non-time-space in the very

heart of time,”17 which cannot be passed on but must be constantly reinvented.

According to this thought-image, then, it is the activity of thinking itself that

forges a narrow path of non-time in the time-space of the mortal human.

Thus, we see that the attempt to open the battlefield outlined by Kafka characterizes

the direction that Arendt's reading of Kafka takes. However, citing an

insertion from Kafka's text, Arendt emphasizes that “this is only theoretically

so”18 - so […] aber nur teoretisch ist.19 According to Arendt, it is more likely that

“he” - unable to find the diagonal - perishes from fatigue, “aware only of the

existence of this gap in time which, as long as he lives, is the ground on which

he must stand, though it seems to be a battlefield and not a home.”20 Moreover,

Arendt clarifies that her aim is to confront “the contemporary conditions

of thought” with the help of a metaphor. She emphasizes that her claims apply

only to mental phenomena, in other words, to thought in time, and cannot be

transposed to historical or biographical time. But fragments from the ruinous

landscape of biographical and historical time can be touched and sheltered by

thought and memory and saved into the (previously noted) “small non-timespace

in the very heart of time.”

About me

. May 23rd 2008

. Music: Duster; Radiohead; Coma Cinema; hey, nothing; Helvetia and others

. Movies, shows: Donnie Darko; Where The Wild Things Are; Alice in Borderland;

Killing Eve and others

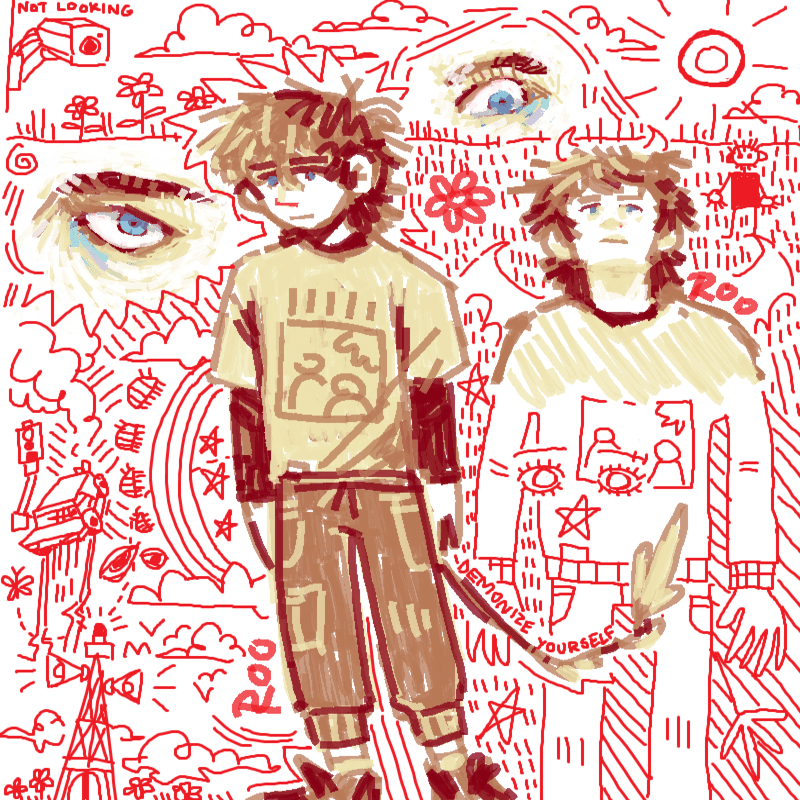

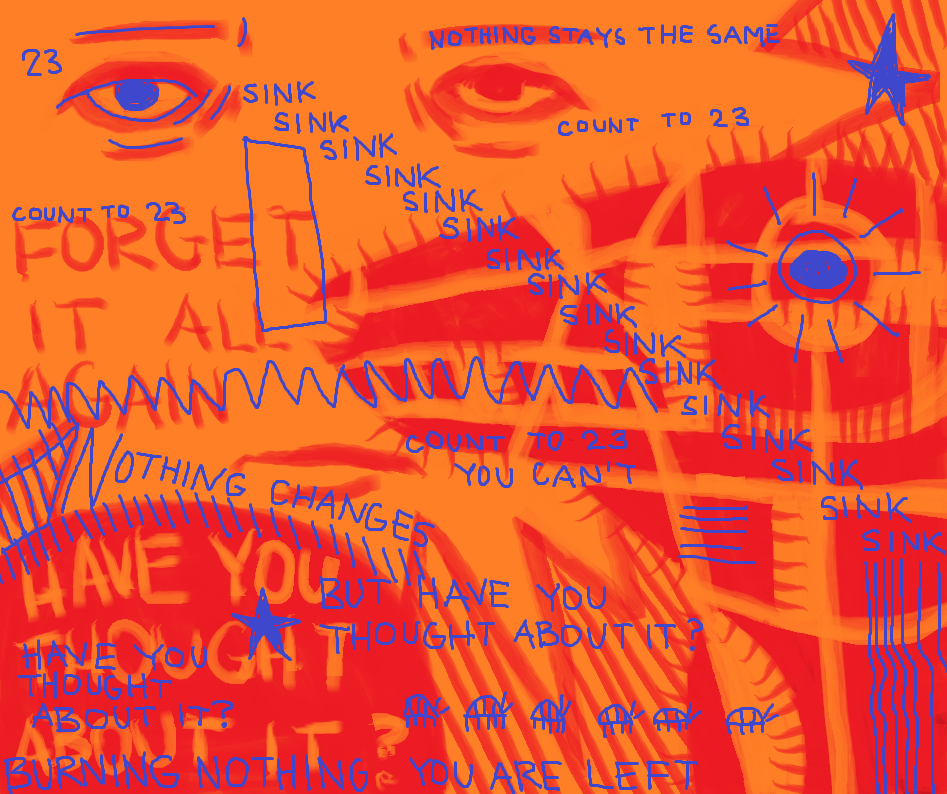

. Traditional & digital art - Ibis Paint X, Krita, Drawception, MS Paint

. Videogames: Disco Elysium, Dredge, Minecraft

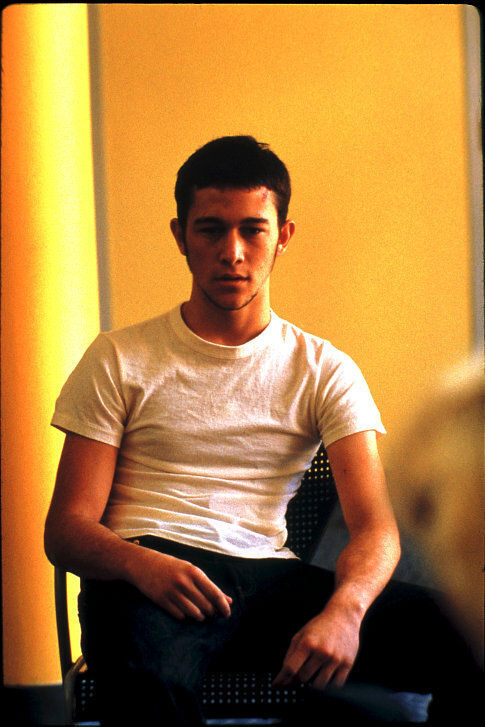

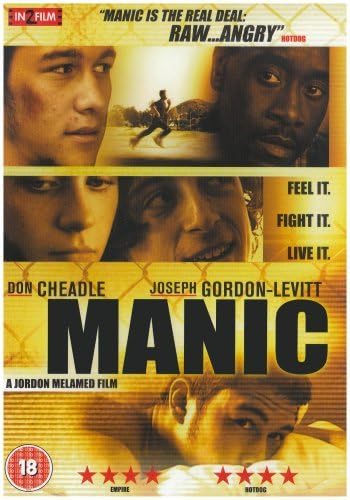

References

Manic (2001)

"It's like ignorance is bliss and this place is fucking Disneyland."

https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0252684/Spotify playlists

Coded with VSCode and GitHub by me, 2025